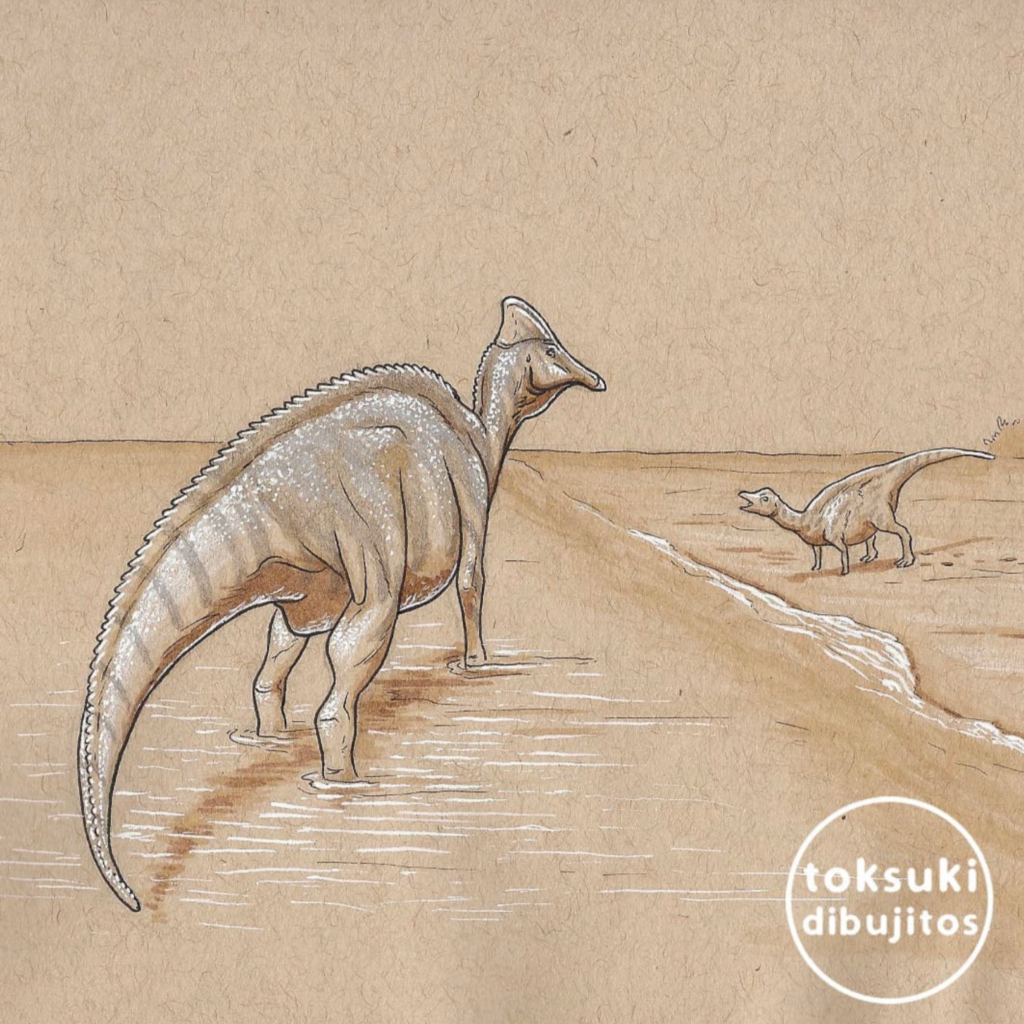

Artist depiction of Ajnabia odysseus. Credit: @i-draws-dinosaurs

Ajnabia odysseus, a recently described herbivore of the Hadrisauridae family, is thought to have performed a remarkable migration journey to colonise Gondwanan Africa. Research suggests these duck-billed dinosaurs may have been more aquatically capable than previously thought.

Hadrosaurids, herbivorous ornithischians often named the duck-billed dinosaurs, had a number of physiological characters that make them instantly recognisable to dinosaur enthusiasts today; the flat-snouted, elongated face was perhaps best fashioned by Lambeosaurus; Tsintaosaurus sported a unicorn-esque crest upon its forehead; Parasuropholous and Charonosaurus displayed a rear-facing, tubular protrusion upon the head. One feature that unites the Hadrosauridae family is facultative bipedalism, the ability to adopt a two-legged gait. Bipedalism may not have been the hadrosaurids’ most remarkable method of locomotion, however; pre-21st century, it was widely accepted that hadrosaurids were largely aquatic.

Early theories of aquatic hadrosaurs made reference to the broad tail acting as a paddle or buoyancy aid, and delicate teeth as described in Hadrosaurus minor implying a diet of succulent aquatic plants. It wasn’t until the late 1900s that the attitude towards aquatic hadrosaurs began to shift, when new publications and discoveries including that of Maiasaura came to light. Eventually, paleontologists were of the understanding that hadrosaurs were primarily terrestrial but may have ventured into water to escape predation or while foraging.

The discovery of Ajnabia odysseus in 2020, however, suggested some hadrosaurs may have traversed much deeper waters. The first hadrosaurid to be described from Africa, A. odysseus was discovered by Longrich et al. in Morocco and the findings published in Cretaceous Research. The genus name Ajnabia, a nod to the Arabic word for foreigner, ‘Ajnabi’, makes reference to the unexpected geography of the findings. Previously, hadrosaurids were thought to have occupied Laurasia (Triassic supercontinent formed of North America and Asia). A. odysseus is thought to have inhabited Gondwanan Africa, which had no land connected to Laurasia. Longrich et al. were then faced with the question: how did hadrosaurids colonise Gondwanan Africa?

Hadrosaurs had dispersed from Lauraisa to South America and Antarctica, but this is the first report of long-distance aquatic migration; “As far as I know, we’re the first to suggest ocean crossings for dinosaurs.” (Longrich et al. 2021). Migration from Laurasia to Gondwana would have comprised crossing the Thethys Sea which, at its shortest length from southern Lauraisa to northeastern Gondwana, would have been at least 500km. Long-distance overwater rafting, whereby species are incidentally migrated upon floating debris, has been offered as an explanation for long-distance mammal migration but it is unlikely these large hadrosaurs could have been supported by debris across such a distance. While it is conceivable that hatchlings or juveniles could have been supported by marine debris, this would not have been sufficient to establish a viable population.

Given several large animals are known to have dispersed across marine barriers, it is not entirely inconceivable that these large dinosaurs could have traversed such a distance to colonise Gondwana; hippos are thought to have colonised Madagascar after crossing approximately 300km across the Mozambique channel; during the Pleistocene, elephants populated several oceanic islands including Cyprus, Crete, and Sardinia.

“Importantly, over millions of years, highly improbable, once-in-million-years events become likely, even probable” (Longrich et al. 2021).

References

Ali, J.R. & Vences, M. (2019) Mammals and long-distance over-water colonization: The case for rafting dispersal; the case against phantom causeways. Journal of Biogeography, 46(11), 2632-6.

Cruzado-Caballero, P., Pereda-Suberbiola, X. & Ruiz-Omeñaca, J.I. (2010) Blasisaurus canudoi gen. et sp. nov., a new lambeosaurine dinosaur (Hadrosauridae) from the Latest Cretaceous of Arén (Huesca, Spain). Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences, 47, 1507-17.

Cruzado-Caballero, P. & Powell, J. (2017) Bonapartesaurus rionegrensis, a new hadrosaurine dinosaur from South America: implications for phylogenetic and biogeographic relations with North America. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 37(2), e1289381.

Erickson, G.M., Krick, B.A., Hamilton, M., Bourne, G.R., Norell, M.A., Lilleodden, E. & Sawyer, W.G. (2012) Complex dental structure and wear biomechanics in hadrosaurid dinosaurs. Science, 338, 98-101.

Longrich, N.R., Pereda-Suberbiola, X., Pyron, R.A. & Jalil, N. (2021) The first duckbill dinosaur (Hadrosauridae: Lambeosaurinae) from Africa and the role of oceanic dispersal in dinosaur biogeography. Cretaceous Research, 120, doi: 10.1016/j.cretres.2020.104678.

Mateo, P., Keller, G., Punekar, J. & Spangenberg, J.E. (2017) Early to late Maastrichtian environmental changes in the Indian Ocean compared with Tethys and South Atlantic. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 478, 121-38.

Ostrom, J.H. (1964) A Reconsideration of the Paleoecology of Hadrosaurian Dinosaurs. Earth Sciences, 262, 975-97.

Leave a Reply